Blog: How trade agreements can contribute to creating a global circular fashion economy

Brussels, 1 April 2020.

By Josefine Koehler, Policy Officer at Ecopreneur.eu

In the fifth of our blog post series about circular fashion, Josefine Koehler explains two ways for trade agreements to contribute to a global circular fashion economy.

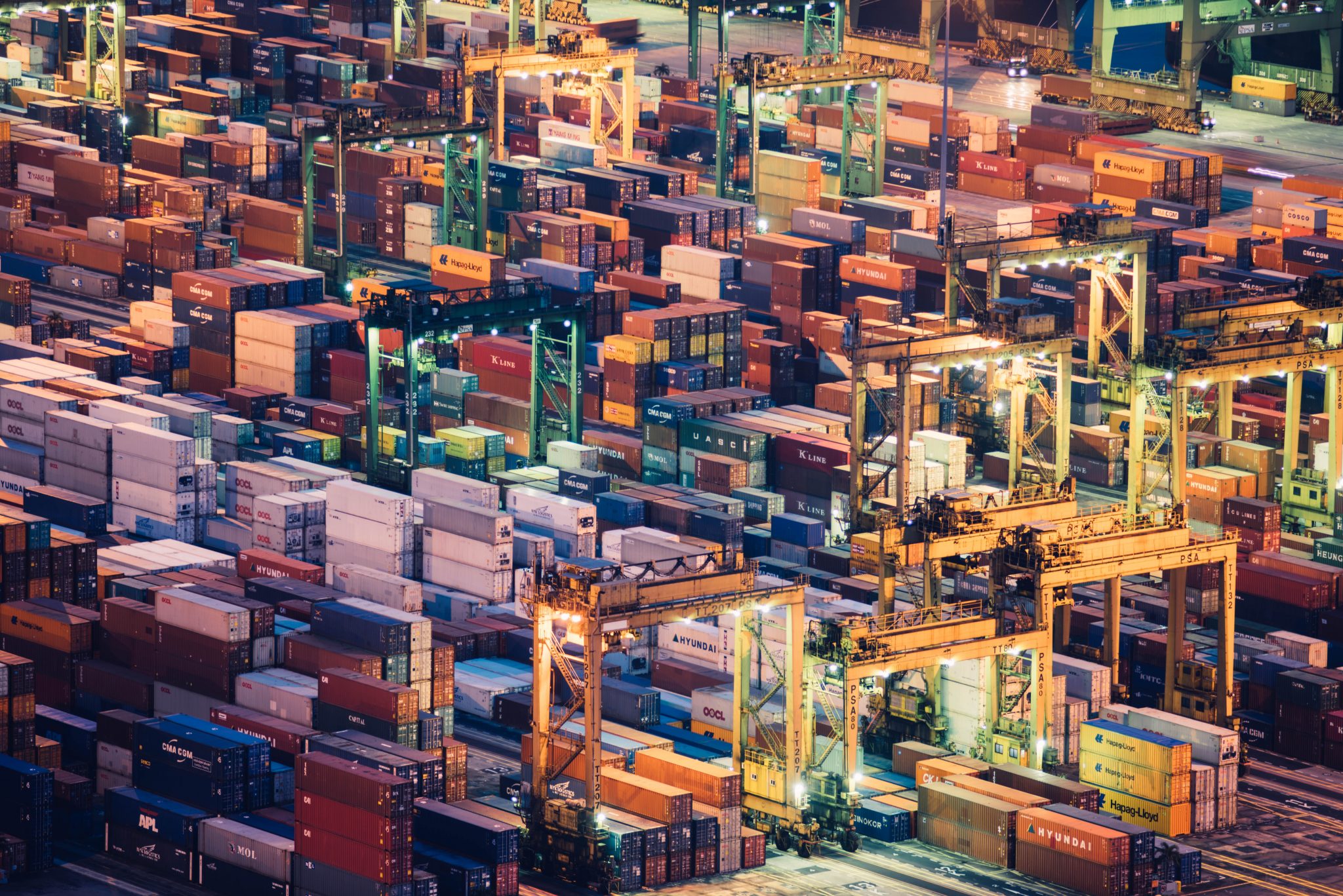

The textile industry is globally interconnected. Different steps in the supply chain, like sourcing the raw material, producing the fabrics and tailoring the garments might take place in different countries before they get distributed, perhaps sent again on an international journey. Europe sources half of its imported goods (with a total value of €166 billion in 2018) from non-EU countries1 – about 70% is supplied by Asian countries like China, Bangladesh and Cambodia2,3.

Where most of the sourcing and production is done outside the EU, this is also where most of the impacts take place4. Textiles are responsible for 8% of global CO2 emissions5. In addition, with land use, raw material use and pollution, the textile industry has the fourth highest overall environmental pressure of all sectors4. On top of being exposed to environmental pressures, workers, of which 70% are women, report “long working hours, low wages, lack of regular contract, and systematically hazardous conditions”2.

A transition towards a more resource efficient and circular economy has broad linkages with international trade6, in general and especially for textiles. This is why trade agreements can contribute to creating a global circular textiles economy. With Europe aiming for a circular economy, with a Circular Textiles Strategy, trade agreements play a crucial role in a twofold manner:

First, European trade partnerships can serve to encourage and support other continents to adjust and rethink their standards as well as to cope with resulting structural changes of the economy and the trade itself. For instance, introducing a tax shift from labour to resources in the EU is expected to impact trade, as would a carbon adjustment mechanism at the EU border. Both are desirable policies that would impact foreign suppliers.

While leap-frogging to a new economy seems possible, much more research is needed to determine the impact of EU circular textiles policies on supplying economies, as we concluded in our recent research note Circular Fashion and Textile Producing Countries7.

Second, with 73% of the textile waste being landfilled or incinerated8, trade can be an opportunity to channel these waste flows to destinations with comparative advantage in sorting and processing these materials6. Doing so, local economies are strengthened, through e.g. job creation. The estimate from the EPA states that 10.000 tons of (mixed) waste materials can create 36 jobs when recycled compared to 6 and 10 jobs if only landfilled or incinerated9. Furthermore, impacts from landfilling, like chemicals seeping into the soil and groundwater, and those from incineration contributing to global warming and air pollution, could be avoided.

However, such benefits have to be weighed against additional potential environmental impacts through shipping textile waste overseas again in order to prevent a rebound effect. Also, exporting valuable waste streams only from an economic perspective should be avoided, especially to countries with lower environmental standards. And locality should be prioritised as it is a fundamental aspect of circularity: one of its principles is to keep the cycles as small and close as possible as to make them resilient – the economic importance of which is emphasised by the current Covid-19 crisis. In short, a trade agreement should only be in place if it respects high social and environmental standards.

These aspects should be considered in current discussion about increasing international trade barriers for textile waste imports, like anti-dumping policies, which include semi-finished products, like clean fibres, clippings as well as sorted textile residues. Such are already imposed by China, India and Kenya10,11,12. These anti-dumping policies are a result of the rising production and consumption in developing economies, which makes them less dependent on the EU and prioritising local waste management.

Transition solutions which are compatible with social and environmental criteria can be a step on the journey towards circularity, bringing value for both sides. Therefore, expanding trade agreements for exporting textile waste to producing and developing economies, should only be a transition solution until they are independent of Europe and/or until Europe can deal with the amounts of textile waste by itself, through scaling up reuse models, expanding recycling capacities or regulating the market demand with strong circular economy policies.

Read Ecopreneur.eu’s Circular Fashion Advocacy report to find out more about how strong circular economy policies will transform the sector. Or explore our recently published research not on Circular Fashion and Textile producing Countries.

References

1 European Commission eurostats (2019). Where do your cloth come from? Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20190422-1

2 European Parliament (2014). Workers’ conditions in the textile and clothing sector: just an Asian affair? Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/EPRS/140841REV1-Workers-conditions-in-the-textile-and-clothing-sector-just-an-Asian-affair-FINAL.pdf

3 Statistica (2019). Leading suppliers of clothing imported into the European Union (EU-28) from 2015-2018. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/422241/eu-european-union-clothing-import-partners/

4 EEA (2019). Textiles in Europe’s circular economy, retrieved from https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/waste/resource-efficiency/textiles-in-europe-s-circular-economy

5 Quantis (2018). Measuring Fashion – Environmental Impact of the Global Apparel Footwear Industry Study. Retrieved from https://quantis-intl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/measuringfashion_globalimpactstudy_full-report_quantis_cwf_2018a.pdf

6 OECD (2018). International Trade and the Transition to a more Resource Efficient and Circular Economy: A Concept Paper. Shunta Yamaguchi. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/847feb24-en.pdf?expires=1585743268&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=0C30811F7AED71CCD20741DE747FC34B

7 Ecopreneur.eu (2019). Circular Fashion and Textile Producing Countries. Available at https://ecopreneur.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/EcopreneurEU-Research-Note-on-Circular-Fashion-Impacts-26-2-2020.pdf

8 EMF (2017). A New Textile Economy. Retrieved from https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

9 EPA (2002). The Resource Conservation Challenge – Campaigning against Waste. Retrieved from https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/10000KXG.PDF?Dockey=10000KXG.PDF

10 Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Republic of Kenya (2019). National Sustainable Waste Management Retrieved from http://www.environment.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Revised_National_Waste_Policy_2019.pdf

11 CNBC (2018). The world is scrambling now that China is refusing to be a trash dumping ground. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/16/climate-change-china-bans-import-of-foreign-waste-to-stop-pollution.html

12 The Economic Times (2019). India imposed anti-dumping duty on 99 Chinese products as of 28 Jan: Commerce Ministry. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/india-imposed-anti-dumping-duty-on-99-chinese-products-as-on-jan-28-commerce-ministry/articleshow/67831165.cms